It's well after dark, and only a glimmer shines from chemical light sticks attached to the masks and left hands of 21 men in scuba gear. We're riding with them aboard a patrol launch that sweeps in parallel to an unlit coastline. Lashed to its seaward side, a small rubber craft bounces along. Lt. Michael Massa barks a command, and the men tumble into the rubber craft. One by one, at 25-yd. intervals, they roll out again into the sea spray. At the end of the run, the green lights glow in a long, straight line.

Massa raises his voice to be heard over the engine roar. "We train these men to regard the water as the only safe area there is. Everybody else in the military trains to regard the water as a danger area--even the Marines. The advantage for us is that if we are pursued, or tracked, or chased or being shot at and we retreat into the water at night, the bad guys aren't going to follow us."

As he speaks, the patrol boat circles to begin the recovery operation. Two men perch in the rubber craft, trailing a large elastic lasso just above the water. As the vessels pass, each swimmer throws his left arm through the loop and is flung aboard the rubber craft before vaulting immediately into the larger boat.

SEAL Team Five rehearses aerial cast and recovery from cargo bay of CH-46 helicopter. Team members seize rope ladder as it drags through water at 5 mph.

We're watching BUD/S Class 201 complete its eighth week of phase-one training at Naval Amphibious Base Coronado, California. Squatting on the boat's transom, the men are exhilarated. They're getting their first taste of combat tactics. Of the original 120 students who entered the program, only these 21 have made it this far. Each has months of further training before the coveted SEAL trident emblem is pinned to his uniform. But they've already learned the meaning behind the SEAL motto: "The only easy day was yesterday."

For underwater demolition missions, a SEAL uses LAR V apparatus. Chest-mounted oxygen rebreather permits limpet mine to be strapped to his back. For navigation, Tac Board combines compass, depth gauge and watch.

Indeed, as the Cold War becomes yesterday's news, the SEALs--special-warfare commandos of sea, air and land--have stepped up to heightened responsibilities. In today's military climate of hair-trigger instability, special-operations personnel are being called upon more than ever before.

That's just fine with Rear Adm. Raymond C. Smith, who heads Naval Special Warfare Command. Smith is the Navy's top SEAL. "It's a great time for us," he says. "We've got great new craft coming on line, new guns, upgraded scuba gear. We're well funded, so our government has put great faith in us. And we've got to keep doing things right."

After speaking with us, Smith, age 53, leads a group of SEALs-to-be through a brutal physical-training class of his own devising. But he marvels at the quality of individuals who apply for SEAL training. Competition is fierce just to sign up for the Basic Underwater Demolition/SEAL, or BUD/S, program.

BUD/S includes the infamous Hell Week, during which students train continuously for six days with a total of 4 hours of sleep. After nine weeks of conditioning, BUD/S students focus on diving and land-warfare techniques.

BUD/S graduates attend the three-week Army Airborne School at Fort Benning, Georgia. They then join a SEAL team for another six to 12 months of on-the-job training.

Combat swimmers get a ride on SEAL Delivery Vehicle Mark VIII.

U.S. NAVY PHOTO BY LT. CMDR. MIKE WOOD

This training stresses insertion and extraction, critical routines that SEAL teams practice relentlessly. Off the California coast, we watch from a safety boat as SEAL Team Five conducts aerial cast and recovery with a CH-46 Sea Knight. Slowing to 5 mph, the big naval helicopter stoops low as SEALs launch a small rubber boat out of its rear cargo door. The commandos then hurl themselves into the water.

Surface approaches often involve small rubber craft such as this Zodiac.

The CH-46 soon wheels in a wide circle, and the recovery drill begins. From the rear ramp trails a rope caving ladder. Each SEAL must grab the ladder and quickly clamber into the cargo bay. The operation is hair-raising, as prop-wash water sprays our boat and a 6-ton assault chopper looms 5 ft. above the waves. Yet this is actually one of the gentlest ways to move SEALs in and out of the water.

Originally fielded for counterterrorist operation, High-Speed Boat can top 50 mph.

Besides commercial climbing gear, team members utilize a Spie rope with integral ring attachments that can hoist up to 10 men at a time. In addition, SEALs have discarded older rappel lines in favor of a thicker so-called fast rope. Describing aerial insertion with these 50- or 90-ft. cables, Petty Officer 1st Class Chris Hinkle says, "All we need for equipment are gloves and a helmet. We grab the line and go. Our hands are the only attachment we have. About halfway down, you start squeezing your heart out to slow down. If you do it right, when you get to the bottom, your gloves are smoking."

SEALs must master parachute insertion as well. Standard static-line jump operations are conducted with the MC1-1B 35-ft.-dia. round parachute. For drops from higher altitudes, SEALs free fall with the MT1XS rig, a 370-sq.-ft. chute oversized to buoy an extra 60 to 120 pounds of gear. Jumps from above 13,000 ft. require the use of the Twin-53 oxygen bottle.

Desert Patrol Vehicle can hit 80 mph

Once they hit the water, of course, SEALs are in their element. SEAL frogmen are famous for the LAR V rebreathing apparatus that allows them to swim without leaving surface bubbles. For missions below 30 ft., divers strap on a mixed-gas rebreather.

Currently, mixed-gas operations are taught only at SEAL Delivery Vehicle (SDV) units. The SDV Mark VIII--known to SEALs as the Eight Boat--is a submersible that carries combat swimmers and their cargo inside a fully flooded compartment. The vehicles launch and return to dry-deck shelters installed on host submarines. Inside an Eight Boat, the only vision comes from obstacle-avoidance sonar and standard Doppler radar.

SEAL operations call for a spectrum of equipment--from high-altitude parachute gear, to alpine and desert uniforms, to stealthy amphibious-approach apparatus.

Meanwhile, free-swimming frogmen carry a so-called Tac Board, which combines compass, depth gauge and watch. SEALs will soon navigate with the MUGR, a Miniature Underwater GPS Receiver with a floating antenna.

SEALs also carry a variety of pistols, soon to include the .45-cal. Offensive Handgun System (see Tech Update, page 31, June '94). SEALs view handguns as secondary weapons, however. "To be realistic," says one member, "if you're in a combat environment where people are out there with assault rifles and heavy machine guns, your [stuff] is pretty weak if you're out there with a handgun. A handgun would typically be used for escape and evasion, which means that everything's gone to hell."

SEALs also carry a variety of pistols, soon to include the .45-cal. Offensive Handgun System (see Tech Update, page 31, June '94). SEALs view handguns as secondary weapons, however. "To be realistic," says one member, "if you're in a combat environment where people are out there with assault rifles and heavy machine guns, your [stuff] is pretty weak if you're out there with a handgun. A handgun would typically be used for escape and evasion, which means that everything's gone to hell."

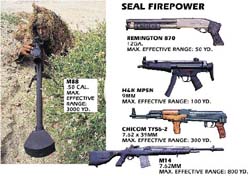

For close-quarter battle, SEALs often rely on the Remington 870 pump shotgun, firing 2-3/4- and 3-in. magnum shells. When targets lie at longer range, sniper operations call for such weapons as the McMillan M88, a single-shot rifle that fires a huge 700-grain projectile--with a muzzle velocity near 3000 fps. "It's a beast," comments Petty Officer 2nd Class Scott Canaan. "You fire it and somebody knows they're getting shot at."

One result of combat experience in the Persian Gulf has been a new regional focus for the six standard SEAL teams. SEAL Team Three, for example, is equipped for Southwest Asia and is the only team with the Desert Patrol Vehicle, or DPV.

This 2x4 Chenowth vehicle carries three. Powered by a 2165cc gasoline engine, it can reach 80 mph. Gussets and bracing on the frame, coupled with high wheel travel, provide a surprisingly smooth cross-country ride. Three weapons stations--two forward and one rear--can accept the Mk.19 grenade launcher, M2 .50-cal. machine gun and the M60 7.62mm gun. In addition, two AT-4 anti-armor missiles are carried on the upper cage, while side baskets provide space to hold Stinger surface-to-air missiles.

As the DPVs of SEAL Team Three snarl across the sands, they seem to capture the aggression, enthusiasm and fearlessness that mark Naval Special Warfare Command. These land vehicles also symbolize the SEALs' expanded range of tasks and capabilities. "There's more to being a Navy SEAL nowadays than just being a great combat swimmer," says Smith. "It's no longer like it was years ago. Special Operations--the Green Berets and the Rangers and us--are held to a higher standard." One they seem to be meeting.